A short version of this article was published in The Land magazine’s summer edition 2015. A PDF of the full version below can be downloaded here:Northern Governmental Organisations.

Northern Governmental Organisations: between the free market and the nation state

Samarendra Das and Miriam Rose

The NGO sector is one of the world’s largest industries. In 2009 there were 3.3 million NGOs (or 1 for every 400 people) in India alone,1 with money pouring in from Intergovernmental Organisations (IGOs), Western donor agencies and philanthropic funds.

Though some critiques of the big NGOs and humanitarian aid have reached the mainstream media in recent years, the general Western perception is that NGOs are doing important and effective work on behalf of millions of deprived people without a voice.

This article gives an alternative perspective. Based on conversations with grassroots activists and marginalised communities in India and Africa over many years of our work on extractive industries, we draw together the common critiques of advocacy and development NGOs in the ‘Third world’ or ‘global South’ – from their role in dividing and co-opting people’s movements by professionalising activism, to their lack of accountability to the people they claim to represent. We show that, behind the ‘rights based’ rhetoric, NGOs consciously or unconsciously serve the neoliberal interests of donor countries, institutions, and even companies.

Of course not all NGOs are the same, and some are much closer to the needs of the people than others. But it is fair to say that there are consistent commonalities in the modus operandi of the NGO sector – which is Western funding led, competitive, and project based, when compared to the people’s movements – which are usually unfunded, and fight for structural changes and emancipation from oppressive forces, rather than reformist goals. This is not an attack, but an appeal for real solidarity with the marginalised people of the world which gives them dignity and visibility, and operates on their terms.

History of the NGO sector

The prevalence of NGOs can be traced to the 1980s, as the ‘development’ and ‘structural adjustment’ policies of the World Bank and Northern nation states gained importance. NGOs were seen as a better way to deliver ‘development’, with a less overtly colonial overtone than Western (or Northern) states themselves. They were heavily funded by the World Bank and national aid programmes to deliver welfare services in the place of the nation state.

By the 1990s ‘structural adjustment’ had already been largely discredited for exacerbating poverty, and the post Cold War period brought a trend towards ‘democracy aid’ – projects that combined a neo-liberal agenda with the need for western democratisation and a narrative of participation. Since many of the big NGOs had lost their credibility with local communities and foreign governments, funders began to favour Advocacy NGOs and ‘Civil Society Organisations’ (CSOs) – smaller local organisations that were perceived as more legitimate and as having a better mandate from communities. In reality many of these CSOs were not ‘bottom up’ but were simply local partners of the larger NGOs, funded and controlled by them.

The noughties shifted the priorities again towards NGOs working with business to promote Corporate Social Responsibility. In 2005 the UN General Assembly unanimously adopted a resolution ‘Towards Global Partnerships’ which encouraged tripartite partnerships of business, NGOs and government to ‘promote development’.

Zambia

In December 2013 we visited Zambia: Africa’s largest copper producing nation, on a research trip to link with communities affected by the pollution and low labour standards of Vedanta’s copper mining subsidiary Konkola Copper Mines (KCM). We were immediately struck by the number of NGOs operating in the country – where NGOs and churches are Zambia’s third largest employer after mining and the State. Though the poorest communities are in the Copperbelt and the rural areas, the majority of NGO offices are in the capital Lusaka. People in the Copperbelt complained to us that international and local NGOs had come to their communities, done surveys, carried out workshops, or gathered evidence for reports and funding, never to be seen again.

NGOs often appeared to be doing the minimum necessary to engage the participation of communities, even giving money in exchange for their cooperation. One Zambian activist we spoke to alleged that Action Aid employees had bought community members beer in exchange for giving statements against a mining company. Another man working for a small Chingola based organisation told us how partnering with larger NGOs had affected their relationship with the local communities:

“a lot of NGOs came here in Chingola and used us. They come here and collect information and they go just like that. Now the community is hating us”.

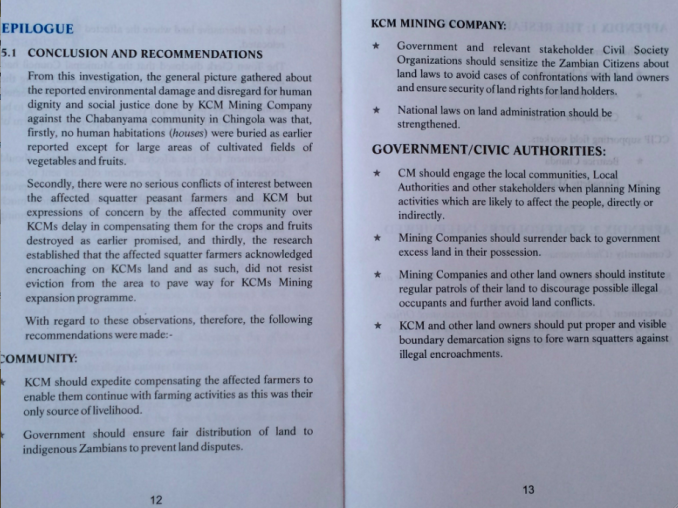

The lack of accountability and transparency in relationships between large and small NGOs and the community was highlighted in another instance. Workers in a local CSO showed us a report which they had been funded by Action Aid to research and write, on KCM’s dumping of mining waste on local communities. Shockingly, the conclusions of the report stated that ‘squatter’ farmers should be removed from the land and the company should increase its security controls. We confronted Action Aid’s Zambia head with the report, who was appalled, telling us that they were supposed to use Action Aid’s pre written conclusions to fit with an existing campaign! In other words the local group were not supposed to show initiative, but simply do the ground work for a pre-determined narrative controlled by the central funding body. Meanwhile the community themselves had absolutely no control over the discourse allegedly written on their behalf.

The lack of accountability and transparency in relationships between large and small NGOs and the community was highlighted in another instance. Workers in a local CSO showed us a report which they had been funded by Action Aid to research and write, on KCM’s dumping of mining waste on local communities. Shockingly, the conclusions of the report stated that ‘squatter’ farmers should be removed from the land and the company should increase its security controls. We confronted Action Aid’s Zambia head with the report, who was appalled, telling us that they were supposed to use Action Aid’s pre written conclusions to fit with an existing campaign! In other words the local group were not supposed to show initiative, but simply do the ground work for a pre-determined narrative controlled by the central funding body. Meanwhile the community themselves had absolutely no control over the discourse allegedly written on their behalf.

In turn, the Action Aid head also felt used by the central international organisation. She told us how she felt Action Aid Zambia was being restricted by their foreign funders, and recounted when someone from the Department for International Development (DfID) had warned her not to put too much pressure on British companies operating in Zambia. She had replied that the DfID funded the UK branch of Action Aid, and not the Zambian unit.

We later discovered that Michael Lynch-Bell, a director of disgraced mining company Kazakmhys2 (implicated in the fraudulent activity which resulted in the de-listing of Eurasian Natural Resources Corporation [ENRC] from the London Stock Exchange last year)3 is also an Action Aid board member, and convener of the International Finance & Funding Committee,4 a major conflict of interest for an NGO purporting to hold mining companies to account for their tax evasion, pollution, and human rights violations.

India

The ultimately successful struggle to save Odisha’s Niyamgiri Hills and their indigenous population from Vedanta’s planned bauxite mine has been claimed as a personal victory by many NGOs – most notably Action Aid, Survival and Amnesty. But the involvement of these groups has been controversial and highly contested on the ground.

Indigenous activists have been angered by incidents like Survival’s co-option of a young tribal man, whom they paid and resourced to act as their spokesperson, but who’s exposure to the urban elites ultimately led him to become Vedanta’s PR representative, doing untold damage to the movement.5 Action Aid and Survival’s images of the Dongria Kond tribe were criticised by local leaders for essentialising them and making them look like victims. An Action Aid banner depicting Dongria girls was destroyed by members of the tribal group when they saw it at a rally, as the girl pictured had never agreed to be used in this way. Amnesty’s high profile report ‘Don’t mine us out of existence’ used interviews with Dongria people to ultimately make the recommendation that Vedanta should look for other mountains to mine in the area, a viewpoint to which the Dongria are totally opposed. Local opposition resulted in the recommendation being removed from the final version.

Action Aid have also been criticised for their conflicts of interest in the campaign. In 2003 they accepted a £40,000 (41 lakh Rs) donation from Vedanta subsidiary Sterlite for homeless shelters in Delhi. In 2010 Action Aid’s CSR arm ‘Partners in Change’ was part of a jury which awarded Vedanta a ‘Best Community Development’ award for its ‘good work’ around the same Lanjigarh refinery which they were supposed to oppose6, prompting a protest outside Action Aid’s Odisha office that lasted several days.

Action Aid, widely believed to be a critical and radical campaigning organisation, also has partnerships with major Indian bank ICICI (one of Vedanta’s key funders)7 and the highly controversial oil and gas company Essar Energy who sponsored Action Aid’s Freedom Run in 2011.8

Despite the long local struggle that preceded and followed the involvement of the NGOs at Niyamgiri, the voices of indigenous leaders and local activists did not reach the Western media, which instead consistently quoted Amnesty’s head Peter Frankental or Survival’s director Stephen Corry as an authority on the issue. The strength and expertise of the grassroots communities were made invisible and the NGOs were projected as the credible, reasonable and pragmatic saviours of the poor victims of injustice, speaking on their behalf. This is as patronising to the concerned Western audience, who are denied the opportunity for real solidarity with those affected, as it is to the communities themselves.

Lingaraj Azad, a Dalit activist, and Convenor of Niyamgiri Suraksya Samiti (Niyamgiri Protection Council) in Odisha, India, voices frustration with the lack of real solidarity shown by the NGOs in the Niyamgiri movement:

“NGOs always try to take credit when movement is strong, but when it is weak they aren’t there. When there is severe repression at events like the recent public hearing where the state, police and the company funded elected representatives come together there is no NGO to be seen.”

Veteran grassroots activist from Varanasi, Chanchal Mukherjee gives another example:

“In Rayagada, during the Kashipur movement local activists with no funding created 5000 people strong rallies and cooked for everyone with donated local rice, then NGO workers came and took pictures and claimed it as their own.”

The NGOisation of resistance: undermining the grassroots

The term NGOisation refers to the professionalizing of social action. Chanchal goes on to explain how the rise of NGOs has ”devalued activism” by “making grassroots activists invisible”. NGOs’ emphasis on funding and their connections to the West mean that; “People think the only ‘successful’ activists are the funded ones, so don’t want to get involved with unpaid activism. Those invisible activists will be seen as incapable and it will be asked “why don’t they have funding?”.”

He explains that, unlike people’s movements which are mostly membership based and horizontal, NGOs “rely on hierarchy”. They “pick out individuals and channel money to them creating power structures in movements that were collaborative.” Funded activists assume new priorities, focusing more on reports, and less on the people. This disempowers people “in the village” as “they begin to feel they can’t take decisions by themselves because the ‘boss’ who is funded has to give the final word.”

Chanchal also complains that NGOs keep communities isolated from each other as “they won’t fund the linking of struggles or solidarity between struggles so they restrict the natural expansion of people’s movements”. He compares the ‘project based’ and ‘funding led’ nature of NGO campaigning with his experience of people’s movements: “As grassroots activists we respond to the situation on the ground and will just go to Niyamgiri or anywhere else that needs solidarity. NGOs can’t do this unless they have funding.”

Mohammed Salifu, President of the Kayayei Youth Association of Ghana (KYAG) gives a scathing account of his experience of NGOs in the slums of Old Fadama, in the Agbogbloshie area of Accra, claiming that they have divided the communities by “seeking to hijack, obstruct and subvert our own independent organisational efforts.” He accuses NGOs of imposing themselves on the communities as their leaders and spokespeople, misrepresenting them to governmental bodies and the media, preventing people from taking their own initiative and representing themselves, corrupting ‘weaker’ activists, and making the communities dependent on them.

He concludes: “That is why, increasingly, they are no longer being seen here in Ghana and West Afrika as friends, but rather as blood-sucking parasites and ‘poverty pimps’.”

In whose interest?

NGOs, small or large, operating locally or globally, are a Northern (Western) phenomena. The vast majority of their funding comes from Northern government aid agencies, or international NGOs (who are in turn funded by Northern government bodies and/or donor agencies), and it is to them that NGOs are primarily accountable via funding reports and evaluations of the project criteria, rather than the people they claim to work for or with. In fact it is a misrepresentation to call NGOs ‘Non-Governmental’ since their existence is in most cases intrinsically tied to the state or Intergovernmental Organisation (IGO) funders and their ‘development’ priorities. They also rely on these connections to access decision makers and increase their influence in the global South as well as in the West/North.9. As NGO reports flood into the media and academia this funding also decides research priorities and ultimately the availability of knowledge.

Many academic critics have analysed NGOs role as the ideological vehicle for neo-liberalism and privatisation in the Global South, seeding and normalising these ideas from below, or at the very least failing to name them as the problem. Firoze Manji, a Kenyan scholar and activist famously wrote in 2002 that NGOs ‘assume the missionary position’, preaching a capitalist doctrine in Africa10. Commenting on the contemporary situation he outlines how NGOs have followed the trend of global capital, becoming increasingly centralised, and powerful, and setting up offices in Africa “so as to be perceived as organisations of the South“. Backed with resources far exceeding those of local organisations they are able to “do deals directly with African governments and to speak on behalf of ‘civil society’.” Most importantly, “they offer no challenge to the neoliberal agenda – indeed, their income depends on not contesting that ideology.”

In the 1990s James Petras and other Marxist scholars made powerful critiques of the hierarchical, bureaucratic and ultimately imperialistic nature of NGOs working in Latin America and the global South. Sadly today that critique has all but fizzled out, and many ‘Left’ movements and Marxist parties are now just as guilty of appropriating and undermining people’s movements, such as at Niyamgiri.

Mainstream NGOs will rarely name capitalism, neoliberalism or neocolonialism as the cause of exploitation or poverty. Instead they often reinforce the aid agency’s paradigm that ‘developing’ countries need better governance, accountability and transparency. They focus on specific local problems, issue based campaigns and a ‘human rights’ discourse, rather than the need for fundamental ideological change. In this way they obfuscate the true picture of global power affecting local realities, marginalising the crucial roles of Europe and USA in the outright loot of valuable resources happening on an unprecedented scale, which can only rightly be called neocolonialism.

In a graphic example of the role of NGOs in spreading the neoliberal agenda Lamia Karim’s article ‘Demystifying Micro-Credit: The Grameen Bank, NGOs, and Neoliberalism in Bangladesh’ outlines how the popularisation of micro-finance led to hundreds of NGOs promoting and pushing the concept on marginalised communities, bringing capitalism into ‘the most intimate sphere of the social, the home and women’ and ‘instrumentally appropriating rural women’s traditional values of honour and shame to encourage loan recovery”.11

Corporate Social Relations

NGOs’ dependence on funding, and the increasing competition between them for it, as well as the trend in corporate NGO partnerships (a neoliberal concept which claims an important role for business in society as the power of the nation state has decreased), means many are not averse to receiving corporate funds. But who ultimately profits from these acts of corporate generosity? A trustee of an African disability charity told us how the charity refused to expose child labour at a local mine after the mining company donated a jeep to their work.

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) programmes have become crucial to the success of industry as they reduce the PR ‘reputational risk’ associated with bad press on pollution, human rights abuses and corporate crimes, which can directly affect their share prices.

In 2002 the world’s largest mining company BHP Billiton partnered with Oxfam to help BHP’s employees develop a ‘rights based approach‘ to ‘dealing with people in developing countries’, via courses in Odisha and Andhra Pradesh, where communities were resisting industry.12 Kartik Majhi, an adivasi (tribal) reported how the Oxfam facilitators had originally told them the meeting was about a micro hydro plant and did not make it clear that BHP Billiton employees would be present at the meetings. Years later they discovered that the information they gave about their local struggle against bauxite mining had been used to help the mining company plan for another local mine to which they were vehemently opposed.

The mutually beneficial and close relationship between business and the ‘third sector’ is described by left wing scholar David Harvey as an NGO-industrial complex.

The NGO class

The influx of NGO funding into the global South has another profound effect, creating what Yen calls ‘a safety net for the African petit bourgeouis to survive and maintain their livelihood in the midst of the most appalling economic conditions’13, as NGO’s Northern sourced funding tends to increase when the ground situation becomes worse. NGO workers, who Firoze Manji claims ‘often consist of the well-educated and privileged strata of society‘ form a new class in global South, with power from funding and international connections, as well as control over significant sections of the population.

Chanchal Mukherjee agrees that NGO workers are ‘elites’, adding that as a result “they do not look at issues of gender, race and class in their own organisations. Instead they reproduce patterns of domination and oppression in society.”

Real solidarity

NGOs offer people hope, but often this hope is an illusion. So is there a role for NGOs at all? We would agree with other NGO critics that there could be. What is desperately needed in isolated communities fighting for land rights is real grassroots international solidarity. We have seen through our own work how this can be a powerful support to people’s movements, exposing repressive State and company forces, boosting morale, amplifying their voice, linking up global grassroots struggles, feeding research back to the ground, and of course challenging the (mostly Western) powers who aid and benefit from injustice – the financial institutions, corporations, and government bodies. However, this kind of action must be mandated by, and accountable to the marginalised communities and grassroots struggles, not capitalising on them. It must make them, and not us as Western activists, visible. And it must be mutual, a two way exchange of information and perspectives, not an extractive exercise in capturing romantic and exciting stories to use for our own goals or world-views.

Footnotes:

1http://southasia.oneworld.net/news/india-more-ngos-than-schools-and-health-centres#.U_ogIoVrCKw and http://archive.indianexpress.com/news/first-official-estimate-an-ngo-for-every-400-people-in-india/643302/

3http://www.independent.co.uk/news/business/analysis-and-features/mining-the-darker-side-of-the-london-market-8213987.html

4http://www.actionaid.org/who-we-are/international-board-members

5Romy Kraemer, May 2013, Conflict and Astroturfing in Niyamgiri: The Importance of National Advocacy Networks in Anti-Corporate Social Movements. Organization Studies. vol. 34 http://oss.sagepub.com/content/34/5-6/823.abstract

6 Vedanta’s website (accessed 25/7/11) http://www.southasiasolidarity.org/2011/08/13/strange-bedfellows-for-action-aid/#sthash.Q6GjzZJG.dpuf

7http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2003-11-20/pune/27212224_1_donor-loyalty-programme-karm-mitra-actionaid-india

9KIM D. REIMANN, A View from the Top: International Politics, Norms and the Worldwide Growth of NGOs. International Studies Quarterly (2006) 50, 45–67

10Firoze Manji, The missionary position: NGOs and development in Africa, International Affairs 78 3 (2002) 567-83

11Lamia Karim, Demystifying Micro-Credit: The Grameen Bank, NGOs, and Neoliberalism in Bangladesh Cultural Dynamics 2008; 20; 5

12 http://commdev.org/corporate-australia-building-trust-and-stronger-communities-review-current-trends-and-themes. Corporate Australia Building Trust and Stronger Communities? A Review of Current Trends and Themes Dr Jehan Loza with Ms Sarah Ogilvie Of Social Compass

13Yen, 2000: 51